George Warburton

County Clare's First Professional Policeman

by Michael Mac Mahon

The situation of a policeman is an extremely valuable one to the Irish peasant.

and he would not lightly forfeit it. |

| - Daniel O' Connell in 1825[1]

|

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century very little in the nature of a police service, as that term is commonly understood today, existed in the rural parts of Ireland. Even in Dublin, the seat of English administration and society in Ireland, the police organisation, though "ahead of the various parts of the English metropolis, including the City of London", was still poorly developed.[2] Until a statute of 1715 empowered the Corporation to employ constables and watchmen to maintain the nightwatch, policing in Dublin was performed by the churchwardens in the twenty-one parishes into which the city was divided. Subsequent attempts to reform the watch system crystallised in the Dublin Police Act of 1786. The main purpose of this act was to create a castle-controlled police force by centralising the watch police within a single jurisdiction - the Dublin Metropolitan District, or the area extending radially from Dublin Castle to the Circular Roads. Among other things, the act provided for the appointment of a Chief Magistrate of Police and two divisional justices, who acted in effect as commissioner and assistant commissioners of police.[3] They were empowered to appoint a Chief Constable and ten Petty Constables in each of the four divisions into which the Metropolitan District was divided. In addition they could appoint up to 400 night watchmen and 40 constables of the Watch. Further reforms of the Dublin Police took place in 1808, including the creation of two extra divisions in the city. Thereafter the organisation of the Metropolitan force remained more or less unchanged until a root and branch reform of policing in Dublin was carried out by the Under Secretary, Thomas Drummond, under the Constabulary Act of 1836.[4]

Rural Policing

Outside of Dublin police reform occurred at a much slower pace. Prior to 1814 the maintenance of public order in the countryside was the responsibility of local magistrates and grand jurors drawn from the landed gentry and the rural middle classes. Under their direction was a thinly-deployed network of so-called baronial constables established by Acts of the Irish Parliament in 1787 and 1792. Recruited 'with little regard to their fitness for law enforcement', and having virtually no training in police duties, the baronial constabulary proved manifestly ineffective in the face of the agrarian eruptions that became endemic in large parts of the south and midlands in the early nineteenth century.[5] The problem was compounded by the fact that in times of heightened disorder, some magistrates, fearful of living amongst a hostile population in isolated areas, abandoned their country residences and opted for the safety of the towns.[6] More and more, therefore, the burden of maintaining public order fell upon the army. However, as the demands on the troops became more frequent overtaxed officers and men increasingly made it clear that they had neither the means nor the desire to take on the role of chief suppressers of agrarian crime, a task for which the only reward was public opprobrium[7] . Moreover, as the end of the French war came in sight it was becoming apparent that existing troop levels in the country could not be maintained indefinitely; and by the spring of 1814 the withdrawal of troops out of the country had already begun.

Faced with these changing circumstances, and aware that the legislation governing the baronial constabulary was due to expire in March 1814, Robert Peel, the twenty-six year old Chief Secretary in Ireland, decided to grasp the nettle of police reform. As a short term measure to help combat the spiralling agrarian crime he pressed the government to reintroduce a refined version of the insurrection act, a measure that was first used in 1796 to deal with serious outbreaks of Whiteboy violence.

In its original form the insurrection act was a draconian piece of legislation providing, amongst other things, for the suspension of trial by jury, increased powers for the military, and the imposition of a sunset to sunrise curfew under penalty of seven years transportation.[8] A modified version of the act again appeared on the statute books in 1807 as a temporary measure for a period of three years, but it was never enforced and, in fact, was withdrawn for pragmatic political reasons in 1810 before its expiry date fell due. Now, in the wake of a succession of violent agrarian outbursts in the spring and early summer of 1814, parliament acceded to Peel's request for the reintroduction of the insurrection act, though with some slight modifications.[9] A few weeks earlier the chief secretary had successfully pushed through another, and more far-reaching measure called the peace preservation act, or 'a Bill to provide for the better Execution of the Laws of Ireland by appointing superintending magistrates and additional constables in counties in certain cases', to give it its correct title.[10]

The Peace Preservation Force

The peace preservation act became law on the 25 July 1814. It was designed to deal with situations where the level of crime, though beyond the control of the local magistrates, was still not judged to be of such magnitude as to warrant the draconian provisions of the insurrection act, particularly the confining within their homes, on penalty of transportation, the inhabitants of a whole county. Instead, it authorised the lord lieutenant, acting on his own initiative, or on the application of the local magistrates, to proclaim a district to be in a state of disturbance and 'requiring an extraordinary establishment of police'. Once the district was proclaimed the lord lieutenant could then appoint a 'rapid-reaction' force of special constables, called the peace preservation force (familiarly called "peelers" after the chief secretary), to assist the local magistrates in policing the district concerned. In this way a 'flying column' of up to fifty well-trained trouble-shooters under the command of a stipendiary magistrate - who was himself a full-time professional policeman - could be speedily despatched to a disturbed district when trouble erupted, and withdrawn again as normality was restored. As a hand-picked, mobile, and well-trained body of men charged with tackling serious crime the peace preservation force was a new concept in policing in Ireland and represented the first step towards the creation of a professional police force.

The peace preservation act became law on the 25 July 1814. It was designed to deal with situations where the level of crime, though beyond the control of the local magistrates, was still not judged to be of such magnitude as to warrant the draconian provisions of the insurrection act, particularly the confining within their homes, on penalty of transportation, the inhabitants of a whole county. Instead, it authorised the lord lieutenant, acting on his own initiative, or on the application of the local magistrates, to proclaim a district to be in a state of disturbance and 'requiring an extraordinary establishment of police'. Once the district was proclaimed the lord lieutenant could then appoint a 'rapid-reaction' force of special constables, called the peace preservation force (familiarly called "peelers" after the chief secretary), to assist the local magistrates in policing the district concerned. In this way a 'flying column' of up to fifty well-trained trouble-shooters under the command of a stipendiary magistrate - who was himself a full-time professional policeman - could be speedily despatched to a disturbed district when trouble erupted, and withdrawn again as normality was restored. As a hand-picked, mobile, and well-trained body of men charged with tackling serious crime the peace preservation force was a new concept in policing in Ireland and represented the first step towards the creation of a professional police force.

Despite the possibilities which the new peace preservation force appeared to hold out, the uptake on its services was slow, the magistrates preferring instead the old method - i.e. a military force backed up by the insurrection act. The reluctance to avail of the peace preservation act was sometimes explained by the fact that it conferred no special powers beyond the ordinary processes of the law, whereas the insurrection act, as we have seen, had the effect of restraining people from being absent from their homes, or assembling at night under the dreaded penalty of transportation. But there was another, and probably a more pertinent reason why the local magistrates were sometimes reluctant to request the assistance of the peace preservation force. Until amending legislation in 1818 permitted the exchequer to defray up to two thirds of the expenses, the cost of deploying the force in a disturbed area was levied on the district concerned.[11] When it is borne in mind that these expenses included the salary of the chief magistrate, the rent of his house, and the cost of billeting the men and their horses, it will be seen that the charges could be quite substantial, if not sometimes downright penal.[12]

The peace preservation force was a carefully-recruited force composed of experienced yeomanry officers, and constables drawn mainly from the Dublin police. The men were well equipped with arms including light carbines fixed with bayonets. The strength of the force assigned to any particular district varied according to circumstances from about thirty to an upper limit of fifty men. The Chief or Superintending Magistrate was paid a salary of £700 a year, a Chief Constable £150 and a constable £50. Once he was assigned to a district, the Superintending Magistrate had primacy over all the local magistrates. He was directly responsible to the Lord Lieutenant to whom he submitted a weekly report of his activities. The decision to withdraw the force from an area could be made only on the authority of the Lord Lieutenant after he was satisfied that peace and good order was restored[13]

The peace preservation force was put into service for the first time in September 1814 to deal with a spate of agrarian outrages in the barony of Middlethird in Co. Tipperary. Over the next two years the force was deployed in disturbed parts of counties Limerick, Westmeath, King's County and Louth, and in two further baronies in Co.Tipperary. In the case of the first three counties mentioned, the outrages sometimes reached such a level of intensity that the government was obliged to back up the peace preservation force by the additional measures of the army and the insurrection act.[14]

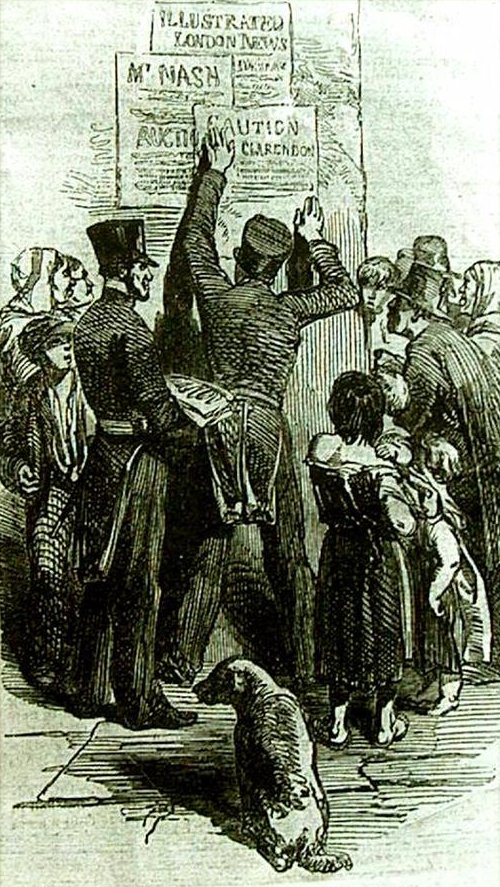

The Peelers in Clare

In the spring of 1816 it was reported that the 'agricultural distress' in Co. Clare was probably unparalleled.[15] The general economic slide that followed the ending of the Napoleonic wars in the previous year was compounded by a dreadful winter that brought near-famine conditions to many parts of the country, but particularly to the poorer and more densely populated regions in the west. As the weeks passed the local newspapers reported unrest and disturbances in various parts of the county, but especially in west Clare where meetings of large numbers of the 'lower orders' were said to be taking place nightly. On 2 March, John Ormsby Vandeleur, a landlord and magistrate at Kilrush, wrote to Dublin Castle to acquaint the chief secretary of serious agrarian turbulence in west Clare. He stated that the system of terror was so established in the western districts that victims were afraid to disclose the names of their assailants, nor would any person venture to take up land at any price where the leases of the tenants had run out, or from which the old occupiers had been ejected.[16] The county, he said, was so thickly inhabited by the 'lower order' that it was extremely difficult to suppress the disturbances, and he urged that a military party be stationed at Cooraclare. The parish priest there, he said, had offered the use of the chapel for a temporary barracks.[17] Three weeks later on 22 March he reported that the outrages were becoming more serious. The peasants, he claimed, were in open hostility to the law and were raiding houses for firearms. To make matters worse, there were very few magistrates in the district, or resident gentry fit to be entrusted with the commission of the peace. The few who were prepared to act had no military back up as there was not a soldier to be found between Ennis and Loop Head, a distance of fifty miles. Threatening notices were being posted everywhere and cattle were being houghed and killed.[18] To add to his frustration, he had found it impossible to get the slightest information about the culprits either by reward or threats. Three days later he wrote again, and this time his plea was even more urgent. On the previous night a party of some thirty men, armed with guns, pistols, and swords had assembled on his lands at Tullavroe. They broke into a number of the houses of his tenants, beat up some of the occupants severely, and set eight of the houses on fire. After torching the houses they went off through the countryside defiantly blowing horns. He complained that troops stationed at Kilkee, who might have prevented this outrage, had been withdrawn, and he was urgently pleading for assistance.[19]

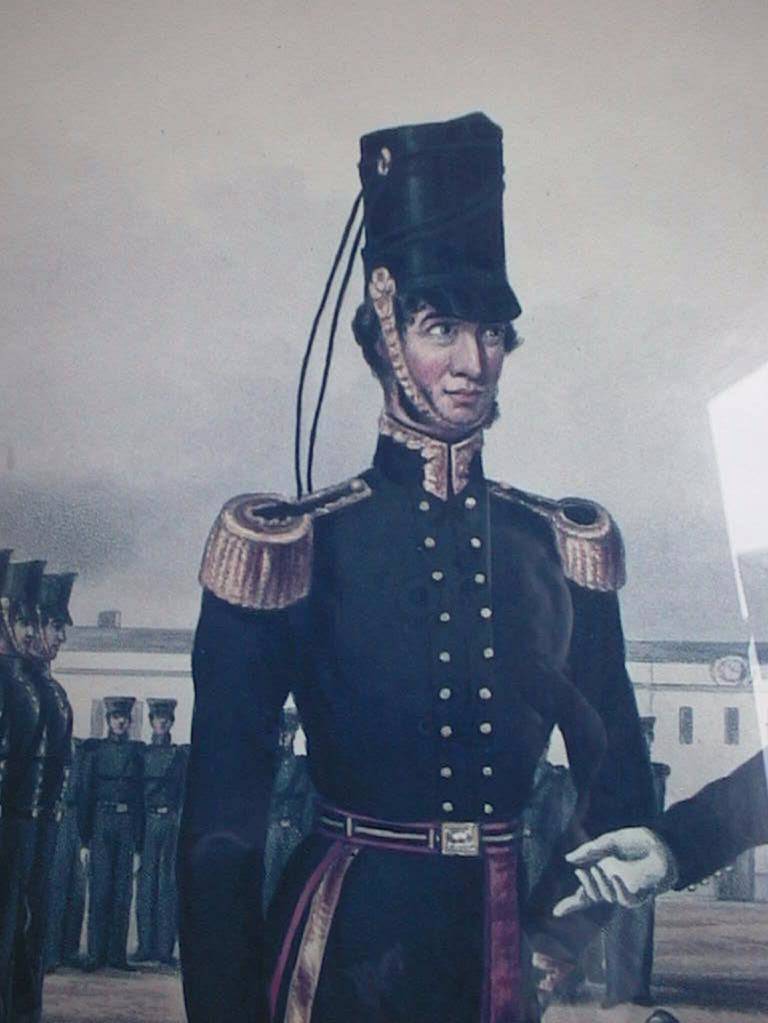

Vandeleur's plea to Dublin Castle was backed up by a resolution from a meeting of the magistrates of the county at Ennis seeking to have the baronies of Clonderlaw, Ibrickan and Moyarta proclaimed. The government responded quickly and by an order dated 3 May 1816 the three baronies were placed under the peace preservation act.[20] By the end of the month a force of fifty constables under the superintendence of chief magistrate, George Warburton, a thirty-nine year old former brigade major of yeomanry in Offaly, were quartered at Kilrush.[21]

We are fortunate that what amounts to a unique personal account of Major Warburton's time in Clare has survived, subsumed in the minutes of his evidence taken before two parliamentary committees set up in 1824 to enquire into the disturbances in Ireland.[22] Though it could scarcely have been foreseen when he arrived in 1816, Warburton was to spend upwards of seven years in Clare, beginning as chief magistrate of the three western baronies, and later of the entire county as the peace preservation act was extended to the baronies of Bunratty and Tulla in 1817, and to all the remaining baronies in 1820.

An intimidating system

Major Warburton's began his testimony by describing the conditions in west Clare as he found them on his arrival in 1816.[23] There was an intimidating system of outrage in place and crimes of flogging and carding were widespread.[24] Oaths of secrecy were being administered, swearing people to assist each other in all their proceedings, and not to betray what they were to do. There were only two or three magistrates in the entire district and they had no means of enforcing the law. The local constabulary force was 'of a very bad description' and totally unequal to coping with persons engaged in disturbances. They could not enforce the magistrates' warrants nor assist them efficiently. In consequence there were large numbers of offenders against whom the magistrates had received information, but they could not be arrested. When he arrived with his men the situation improved. Some of the magistrates came forward and eagerly assisted them. They even rode out with his men at night in an effort to have the culprits arrested.[25]

Major Warburton's claims for the effectiveness of the new police would appear to be well founded. Within two months of their arrival they had collected upwards of 130 sworn informations against a number of Whiteboys, though they succeeded in arresting only fourteen persons.[26] Getting convictions in court, however, proved to be more difficult. A couple of people, who had the courage to come forward to testify against the prisoners were attacked and insulted in the court house, and almost all the cases were lost for want of evidence.[27] Nevertheless the outrages declined, and in June the Ennis Chronicle reported that the inhabitants of Clonderlaw, Moyarta and Ibrickan were 'manifesting a sincere contrition' for the disturbances which had caused the districts to be proclaimed.[28] A correspondent to Dublin castle at this time, however, took a less sanguine view of the situation. He believed that it was the 'great dread of a heavy tax that more than any other cause induced the country people to [return to] tranquillity'.[29] But whatever the reason, the Ennis Chronicle believed that there were well founded hopes for the speedy revocation of the proclamation.[30] The same optimism prevailed right through the months that followed, and in December it was reported that Major Warburton's corps had 'extended its salutary effects to the remotest quarters of the county'.[31] Though this latter claim was probably somewhat extravagant, it seems worth noting that the business at the quarter session court at Ennis in October consisted of 'little more than routine'.[32]

The Priests

It seems of interest to note that, around this time, too, the priests, began to exert themselves in seeking to persuade their flocks to refrain from protest, probably in order to forestall clashes between the people and the new Warburton police. The newspapers give several instances where landlords and magistrates were invited into the chapels on Sundays for the purpose of addressing the congregations and administering oaths of loyalty. For instance, shortly after the arrival of the peace preservation force Fr. Mc Inerney, parish priest of Kilkee, invited Richard Studdert, a local magistrate, to address his congregations at Kilkee and Doonbeg.[33] The magistrate urged the people to refrain from violence and to surrender any arms they might be holding unlawfully in their possession. It was said that afterwards those present 'cheerfully took an oath of allegiance to the king and gave a sworn promise that they would give information on any unlawful activity to some one of the justices of the peace'. In the following weeks other magistrates addressed congregations in the chapels of Coolmeen, Kildysart, Lisdeen, and Kilmurry-Ibrickane.[34] In the latter place, after the local landlord and a magistrate had both addressed the congregation, Fr. Mc Guane, the parish priest, is said to have taken the oath himself and then to have personally administered it to several hundred people.[35]

Warburton told the Inquiry that though he could give several instances in which the priests had assisted him, generally, however, he could not say 'that there was much exertion made'.[36] When asked to expand on the role and influence of the priests he drew some interesting distinctions. With one exception he had found the elderly priests more ready to communicate with him than the younger ones. Significantly the younger ones, he believed, were mostly educated in Maynooth.[37] When pressed further on this point, he said he thought the Maynooth educated clergy were more bigoted, 'more wedded to their system' than those priests who formerly were obliged to go abroad for their education. He had met several priests who had been educated abroad and found them to be well-informed persons.

The people, however, particularly the lower classes, seemed to prefer the Maynooth priests, because, as a class, they were closer to themselves and consequently they knew each other better. He had heard the term 'Protestant priests' applied in a pejorative way to the foreign educated clergy for the reason that they seemed to be more at ease with the gentry than the others.[38]

The Condition of the Poorer Classes

Major Warburton had much to say about the straitened economic conditions in Clare and the rampant subdivision of land that was taking place, especially in the western parts of the county. There the average amount of land held by those at the lower end of the agricultural scale was from one to two acres.[39] Originally the holdings had been larger but many of them had been reduced virtually to garden size as a result of subdivision among sons and sons-in-law.[40] Indeed, so acute was the subdivision in the western parts of the county that much of the countryside 'appeared almost a continuous village, it was so studded with cottages and so divided into these small gardens'.[41] And so great was the density of population that even a partial failure of the potato crop in a bad season would, he believed, cause widespread starvation.[42] He believed that the system of forty-shilling freeholding was another factor that contributed greatly to the subdivision of farms in Co.Clare.[43] Because the forty-shilling freehold franchise extended to persons renting as well as those owning the qualifying amount of land, landlords often recklessly sublet in order to be assured of extra votes at election time.

Where a labourer was hired by a farmer the practice, he said, was that the farmer let him a garden, and the labourer was allowed, at so much a day, to work out the rent. But there was a great number of landless people in the county who had no regular employment.[44] The system of letting land as conacre was therefore widespread. The general practice was that the proprietor of the land ploughed and manured a certain portion of ground, which he did not require for his own use, and let it for a crop or two crops in succession. As the population increased the demand for potato ground became so great that individuals often rented as little as one ridge in a field.[45] The rent was generally very high, from four to ten guineas per acre, but it was the only means whereby a large number of the labouring poor could procure food for their sustenance. Some of the attacks by the peasantry were upon the proprietors of conacre.[46]

Major Warburton gives us valuable information as to the condition of the dwelling-houses throughout the county. The houses of the cottiers and labourers were generally 'very wretched'.[47] They were built of the mud on which they stood, with straw mixed with it.[48] In the boggy parts of the county they were sometimes cut out of the turf. In many cases they had neither window nor chimney. In the three western baronies already alluded to, the quality of the houses was particularly bad, and the wretchedness of the occupants was 'as great as human nature could almost be subject to'.[49] The mass of the population in Co.Clare, he thought, were very miserably provided with food, lodging, and bedding, and the other necessaries of life.[50]

Major Warburton's comments on the state of the houses in Clare is supported by the census returns of 1841, which, for the first time, included a classification of inhabited houses in respect of their condition on a national scale. Four classes of house were adopted by the census commissioners.[51] The lowest, or fourth-class, were described as mud cabins having only one room.[52] Fifty-one per cent of all the inhabited homes in Co.Clare fell into this class as against thirty-seven per cent for the country as a whole.[53]

The Inverness

For the second year in succession the autumn and winter of 1817 was marked by exceptionally bad weather.[54] In October it was reported that much damage had already been caused to the harvest and several fields of potatoes had been lost. Cattle prices were 'ruinously low', and butter markets throughout the country were depressed.[55] In the following spring as food shortages began to bite sporadic outrages were again taking place. At Carrigaholt a large crowd from the village and surrounding area attempted to raid the Inverness, a supply ship, containing butter, pork and bacon. A strong party of police under Major Warburton intervened to protect the cargo, and, in the confusion, three people were killed and thirty-seven arrested.[56]

Notwithstanding the incident at Carrigaholt and some other isolated eruptions the western baronies were gradually returning to a more orderly state. Warburton told the committee that the coastal district of Clare from Kilrush to Galway Bay soon became the most peaceful in the county.[57] The people, he said, showed no hostility towards himself or his subordinate officers.[58] On the contrary, in many instances, they referred to them as umpires in their disputes. During his time at Kilrush he had appointed three days each week to hear complaints:

And I assure the committee, that sometimes the people would stay in my office till ten o'clock at night, and were obliged to come again in the morning. I have had hundreds; in fact my office appeared almost like a quarter sessions, people attended in such numbers.I have known people to come as far as thirty miles.[59]

But if peace was restored to the western baronies, other parts of the county were now showing signs of turmoil. In June Bunratty was proclaimed to be 'in a serious state of disturbance' and Warburton and his 'peelers' were assigned to that barony on the orders of the lord lieutenant.[60]

Bunratty and Tulla

The agrarian unrest in Bunratty was nothing new. As early as 1815 a meeting of the magistrates of the county had petitioned the government to have the insurrection act applied to the baronies of Bunratty and Tulla because of the frequency of the eruptions in both these places.[61] On that occasion the petition was refused, the Lord Lieutenant stating that on the basis of the evidence they had presented he could not consider the situation in Clare to be much worse than usual.[62] As a compromise, however, he directed that a military detachment from Limerick be placed at Newmarket-on-Fergus to assist the local magistrates in preserving the peace.[63]

The agrarian unrest in Bunratty was nothing new. As early as 1815 a meeting of the magistrates of the county had petitioned the government to have the insurrection act applied to the baronies of Bunratty and Tulla because of the frequency of the eruptions in both these places.[61] On that occasion the petition was refused, the Lord Lieutenant stating that on the basis of the evidence they had presented he could not consider the situation in Clare to be much worse than usual.[62] As a compromise, however, he directed that a military detachment from Limerick be placed at Newmarket-on-Fergus to assist the local magistrates in preserving the peace.[63]

The baronies of Bunratty and Tulla would continue to experience a good deal of agrarian turbulencnce and to pose many problems for the police and military during Warburton's service in the county.[64] For one thing both districts contained large areas of mountainous territory which were next to impossible to police in terms of communications and the state of the roads. Feakle, in the outliers of the Aughty mountains was, according to Warburton, "the largest, wildest and most inaccessible district in the county". It had few, if any, resident gentry. The local circumstances made it impossible to pass through that country, particularly at night, unless one were acquainted with the pathways. The people there, he said, were notorious for being concerned in riots at fairs, in illicit distillation, and other lawless activities. Moreover, it was the harbour and asylum of every turbulent and ill-conducted person fleeing from the law; and once they had found refuge there, it was difficult even for a military force to apprehend them. Cratloe, a large mountainous region with an extensive tangle of forest in Bunratty barony, was even more difficult to patrol, and was thus another favourite haunt of the agrarian insurgents.[65] In the early 1820s, according to Warburton, Cratloe was also a centre for much secret 'networking' between the local insurgents and the notorious 'Rockites' from Limerick.[66]

In the spring of 1820 two attempted incursions of 'Ribbonmen' from Galway caused a flurry of activity among the police and military in Clare and on 1 March the entire county were proclaimed under the peace preservation act.[67] Major Warburton's force was increased to 150 and afterwards to 200 men, and each constable was given authority to act as magistrate pro tem with full powers to call out the army if necessary.[68] Among the distinguishing characteristics of the Galway Ribbonmen was the wearing of white bands on their hats and the illegal (and sometimes forcible) administration of oaths, many of which were overtly sectarian in content. However, the incursions proved to be something of a damp squib; the authorities had got advance warning and the insurgent leaders were arrested without much difficulty when surprised by waiting parties of police and military at Killinaboy, and at Cooleen Bridge near Feakle. Following the arrest of the Ribbon leaders, the county entered a period of relative calm until the famine in 1822 caused further eruptions. These would continue sporadically over the following couple of years.

Major Warburton was not unsympathetic to the plight of the poorer classes, believing that straitened economic circumstances lay at the root of much of the agrarian turmoil at this period. He told the Inquiry in 1824 that the people of Clare were a 'better disposed peasantry' than those in the adjoining counties of which he had experience.[69] He believed that the agrarian unrest in the county could to some extent be put down to the distressful condition of the people and the general lack of employment. "I am sure", he told the Inquiry, "that if the people were employed, their thoughts would not be directed either to disturbances or to political discontents; I think that would be the case, at least to a considerable extent".[70]

During the famine of 1822 Warburton was active in co-ordinating measures for the relief of distress. In April he succeeded in persuading the Lord Lieutenant to provide funds for relief in a certain ratio to the amount raised through local subscriptions; and subsequently he addressed meetings of the gentry throughout the county with a view to ascertaining the extent of the distress in each district so that the work of the relief committees could be more effectively focused.[71] In the previous November he was the recipient of an address by the people of Kilrush in appreciation of his efforts on their behalf.[72]

Major Warburton served as chief magistrate of the peace preservation force in Clare from May 1816 until October 1823 when he left on promotion to inspector of police in Connaught.[74] After the new constabulary were put in place the peace preservation force would serve only in disturbed districts under circumstances of "extraordinary necessity". In 1825 a peace preservation force existed only in Tipperary, Cork, and the county and city of Limerick.[75]

While Major Warburton's public life is well documented information on his private life and background is tantalisingly meagre. The Warburtons, it seems, were a branch of an old Cheshire family who held estates in Ireland at Garryhinch, near Portarlington and at Aughrim, Co.Galway. In the few biographical notices that exist the major is described as of Aughrim, Co.Galway, though his eldest son, Bartholomew, was born "near Tullamore" in 1810 while a third son was born in Wicklow in 1816.[76] The major himself was born in 1777, probably at Garryhinch, and in 1806 he married Anna Acton of Westaston, Wicklow.[77] While stationed in Clare in 1817 he expressed a desire to move to Co. Wicklow in order to improve his six children's education.[78] Though his wish was not granted on that occasion he eventually made Wicklow his headquarters when he was promoted to Deputy Inspector General of Police in 1831.[79] He told the Lords Inquiry in 1824 that prior to his appointment to Co. Clare he had served for various periods as a major of yeomanry in King's County, Tipperary, Cavan, Monaghan, Wicklow and Carlow.[80] Four months before his retirement in 1838 he was promoted to Inspector General of Police in Ireland. He retired to Wrexham in England on a pension of £1,000 a year.[81] Robert Peel, when chief secretary in Ireland, had a high opinion of Major Warburton, describing him as "very intelligent and active".[82] It was said that his knowledge of the Irish language was probably one of the considerations which resulted in his posting to Co. Clare in 1816.[83]

Warburton's sons, all of whom left Ireland, became more widely known than their father. Bartholomew Elliot (1810-1851), the eldest son, was a peripatetic writer on historical and literary subjects. He achieved international notoriety with the publication of his travels in Syria, Egypt and Palestine under the title of The Crescent and the Crown, a book that passed through at least seventeen editions. He died tragically on board the Amazon, which caught fire of Land's End in 1852. Another son, Thomas ( ? -1894) became a barrister and was afterwards ordained in the English church. He, too, wrote a number of books, including Rollo and his Race, or Footsteps of the Normans and The Equity Pleader's Manual. George Drought Warburton, the third son, named after his father's brother-in-law George Drought (a Wicklow JP who saw long service as a 'Peeler' magistrate in the city of Limerick, 1821-1836), was author of a number of popular works on Canada. In 1857 he was elected a liberal independent M.P. for the borough of Harwich in Essex. His only daughter became the wife of Edward Spencer-Churchill. Falling into ill-health, he was subject to bouts of severe pain, during one of which he shot himself through the head at the age of 41.[84] He is buried at Iffley, near Oxford.

Major Warburton's official reports and correspondence directed to Dublin Castle during his time in Clare are preserved among the Chief Secretary's Office Registered Papers in the National Archives. To fully explore this voluminous material here would be far beyond the scope of the present paper. It remains but to say that, taken together with the major's evidence to the parliamentary committees in 1824, it constitutes one of the most valuable sources we have for the pre-Famine decades in Clare. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that there is scarcely an aspect of the contemporary political, economic or social life of the county that it does not illuminate. Yet for all that it remains surprisingly neglected by historians.

1 Quoted in Stanley Palmer, Police & Protest in England and Ireland, 1780-1850 (New York 1988], p. 237

2 ibid, p. 81

3 26 Geo. 111. Cap.24. The Dublin Metropolitan District consisted of the land inside the Circular Roads and the land inside the walls of the Phoenix Park.

4 The full title of the Act which resulted in the reform of 1836 and the creation of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) was "An Act for Improving Police in the District of Dublin Metropolis 1836".

5 Connolly, S.J., 'Union Government, 1812-23, in W.E. Vaughan (ed.) A new history of Ireland, v, (Oxford, 1989), 58.

6 When an outbreak of 'Ribbonism' occurred in the Corofin district in 1820 William Fitzgerald, a magistrate, informed Dublin castle that he was moving his family to Ennis because his house was 'low and thatched' !

7 Palmer, Police & Protest, 196.

8 Galen Broeker, Rural disorder and police reform in Ireland (London, 1970), p. 48.

9 54 Geo. 111, c 180 (30 July 1814).

10 54 Geo. 111, c 131.

11 Dispatch from His Excellency the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, to Lord Viscount Sidmouth, dated 5 June 1816, viz. A Statement of the nature and extent of the disturbances which have recently prevailed in Irl. Parl. Papers 1816, ix [479], 569-579. [Hereafter cited as Whitworth to Sidmouth, 5 June 1816.]

12 For instance, the expenses arising from the deployment of the force in Clare for the twelve months from January to December 1817 amounted to £7,573 - Parl. Papers 1818, xvi [75], p.2. Lim. Evening Post, 26 March 1818.

13 Palmer, Police and protest, p. 200.

14 Whitworth to Sidmouth, 5 June 1816. [See footnote 11 above.]

15 Ennis Chronicle, 12 February 1816

16 Vandeleur to chief secretary, 5 February, 1816 ('State of Country Papers', series 1[1796-1830], National Archives 1816/1768/6. Hereafter cited as S.O.C.P., 1.

17 ibid.

18 Vandeleur to Gregory, 22 March 1816, S.O.C.P., 1, 1768/8. [The houghing of cattle was a common tactic used by agrarian insurgents around the country at that time. It involve cutting the tendons in the animals' legs in order to lame them.]

19 The same to same, 25 March 1816, S.O.C.P., 1, 1768/10

20 Parl. Papers 1818, xvi [75], p.2; Ennis Chronicle, 8 May 1816.

21 Whitworth to Sidmouth, 5 June 1816.

22 (a) Minutes of evidence taken before the select committee appointed to inquire into the disturbances which have prevailed in those districts of Ireland which are now subject to the insurrection act [hereafter House of Commons committee, Disturbances Irl., 1825] Parl. Papers 1825 [20], vii. And (b) Minutes of evidence taken before the House of Lords' committee on the same, Parl. Papers, 1825 [200], vii (hereafter Lords' Committee, State of Irl.1825].

23 Lords committee, State of Irl.,1825, p. 79.

24 Carding involved scoring the victim's flesh by the use of the much dreaded carding irons. These were small, wooden boards, or "butter spades", with a bristle of sharp metal spikes on one side. They were designed for combing (i.e.'softening') wool before spinning it into thread. They were known to cause horrible injuries.

25 ibid.

26 S.O.C.P. 1, 1816/1768/34, 37-8. Palmer's assertion (Police and protest, p. 233) that the new police had 'no appreciable effect on either [prosecutions or convictions]' is at odds with several contemporary newspaper reports (see below) and with much of the official correspondence as it relates to Clare at any rate.

27 Warburton to Peel, 4 August 1816, S.O.C.P., 1, 1768/34.

28 Ennis Chronicle, 5 June 1816.

29 Lysaght to Gregory, 5 June 1816, S.O.C.P., 1, 1786/29.

30 Ennis Chronicle, 5 June 1816.

31 ibid., 14 December 1816.

32 Ennis Chronicle, 23 October 1816.

33 Ibid, 5 June 1816

34 ibid, 12 June 1816.

35 Ibid., 19 June 1816

36 House of Commons Committee, Disturbances Irl., 1825, p.162

37 Lords Committee, State of Irl., 1825, p.86

38 ibid.

39 ibid, p.128.

40 ibid, p. 127.

41 Ibid., p.128

42 ibid., p.152

43 ibid, p. 148.

44 ibid., p.129.

45 Lords Committee, State of Irl., 1825, p. 92.

46 ibid.

47 ibid., p.94.

48 ibid.

49 House of Commons Committee, Disturbances Irl., 1825, p.126.

50 ibid.

51 Report of the commissioners appointed to take the census of Ireland for the year 1841, p. xiv, Parl. Papers 1843 (504), xxiv.

52 ibid., p.160. [For an expanded description of this house type see Ó Danachair, 'The bothán scóir' in Etienne Rynne (ed.) North Munster studies (Limerick, 1967), p.489-90.]

53 ibid., pp., xxiii, 160

54 Ennis Chronicle, 19 October 1816

55 ibid, 12 October, 1816.

56 Limerick Evening Post 24 February 1817

57 House of Commons Committee, Disturbances Irl., 1825, p.126.

58 ibid.,

59 ibid.

60 Warburton to ? S.O.C.P. 1, 1834/12-13.

61 Clare Journal, 20 April, 1815

62 Broeker, Rural disorder, p. 81

63 Clare Journal, 27 April, 1815.

64 In response to a wave of houghings and burnings in March 1823 the baronies of Bunratty and Tulla were placed under the Insurrection Act - Warburton to Gregory 25 March 1823, S.O.C.P. 1 2510/26.

65 House of Commons Committee, Disturbances Irl., 1825, p. 163

66 ibid, p.138.

67 Beckwith to Grant 6 March 1820, SOCP 1, 2183/15.

68 Palmer, Police and protest, p. 221

69 House of Commons Committee, Disturbances Irl., 1825, p.126

70 Lords Committee, State of Irl., 1825, p. 82

71 Warburton to Wellesley, 21 January 1822. Chief Secretary's Office, Registered papers (outrages) 1822 no. 4097; same to same 30 April, 1822 no. 941.

72 Limerick Chronicle, 5 December 1821

73 Lords committee, State of Irl., 1825, p. 77.

74 Palmer, Police and protest, p. 249.

75 ibid, p.267

76 Dictionary of National Biography, [DNB] 2, (Oxford University Press, 1975) p.751

77 I am grateful to Garda Jim Herlihy, author of The Royal Irish Constabulary and other publications, for some biographical information on Major Warburton.

78 Palmer, Police & Protest, p. 670 (footnote 79).

79 Clare Journal 20 Oct. 1831

80 Parl. Papers 1825 [129] VIII p. 844

83 Palmer, Police and protest, p. 365. According to the DNB, p. 751, his son George was living with him there in that year.

82 ibid, p. 212.

83 ibid.

84 DNB, 2, p.753.

|

Michael Mac Mahon is a retired Garda Sergeant living in his native Co. Clare. He holds an MA in history and local studies from the University of Limerick and has published a number of booklets and articles on local

history and field monuments. He is a past Vice-President and Honorary Life member of the Clare Archaeological & Historical Society and he served on the

Heritage Council during the period 2000-2005.

|

Copyright Michael Mac Mahon, © 2004

|